The crisis of 2008–2009 demonstrated that the existing mechanism for regulating the global financial system was clearly insufficient. European funds freely participated in the acquisition of derivatives based on American mortgage-backed securities, and the mass nature of these operations went largely unnoticed by rating agencies and regulatory bodies. Substantial coordination was also required at the international level among national regulators. For example, regulators in the United States should have been aware of open credit positions held by American banks, while their Swiss counterparts were expected to monitor the lending activities of local banks. Yet neither had complete information, and both failed to assess the degree of systemic risk facing the global monetary system.

Consequently, various regional and interregional blocs began to emerge, concentrating within themselves independent settlement and payment systems, trade, insurance, and investment infrastructures in order to create regional financial “supermarkets” and to strengthen their autonomy and independence.

In this context, the fragmentation of financial markets became a logical preparatory step towards their digitalisation and the creation—rather than a set of merely recommendatory international norms—of a technically guaranteed jurisdictional space in the financial domain. The establishment of financial supermarkets represented an attempt to restore trust through centralised means. It is noteworthy that 2009 also saw the emergence of the first mathematical model based on decentralised technologies. Thus appeared Bitcoin — not merely a cryptocurrency, but a fully fledged payment system independent of third-party organisations and institutions.

In recent years, cryptocurrency has become an integral part of the global financial system. Increasing numbers of Belarusians are showing interest in digital currencies, viewing them as a means of earning and investment. However, an effective infrastructure for the legal and comprehensive use of such assets in Belarus is still in the process of formation.

On 5 September, the President of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, chaired a meeting on the development of the digital token sector, during which the prospects for establishing a domestic crypto-bank were discussed. According to the participants, such an institution would bring the digital asset market out of the shadows, create the necessary legal infrastructure, and reduce the volume of illegal transactions in the country.

A crypto-bank resembles a traditional bank, particularly in its ability to provide deposit, lending, and settlement services, but with a specific focus on cryptocurrency transactions, services for individuals, and market players such as crypto exchanges and fintech companies. Unlike second-tier banks that interact with crypto exchanges primarily through conventional settlement operations, a crypto-bank would possess a broader range of functions. One of its most significant capabilities would be the ability to verify digital wallets directly.

Currently, second-tier banks do not inspect digital wallets themselves; instead, they request regulatory documents from exchanges to ensure compliance with KYC (Know Your Customer) and AML (Anti-Money Laundering) procedures aimed at preventing money laundering and terrorist financing. A fully fledged crypto-bank would be able to assess cryptocurrency transactions independently, request access to a client’s digital wallet, analyse asset movements on the blockchain, conduct scoring, and evaluate operational risks.

All of this would contribute to higher levels of oversight and security. Furthermore, a crypto-bank could provide additional services such as stablecoin lending, digital asset trading platforms, and custodial storage through third-party services or companies.

However, the practical implementation of this concept faces significant compliance challenges. By their very nature, cryptocurrencies create substantial difficulties in meeting AML and counter-terrorism financing requirements. Blockchain transaction tracing demands considerable resources — the investigation of even a few transaction chains can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Global experience shows that fully integrated crypto-banks within the traditional financial system do not yet exist. The main obstacle lies in regulatory constraints: most jurisdictions do not recognise cryptocurrencies as legal tender. This is due to the absence of deposit insurance in crypto assets and the high volatility that complicates the development of lending or deposit products. The closest analogues to a crypto-bank can be found among some second-tier banks in Switzerland, Singapore, Germany, and the United States, which combine traditional banking services with limited cryptocurrency functionalities..

For Belarus, the most realistic scenario would not be the creation of a separate crypto-bank from scratch, but rather the gradual integration of crypto services into the operations of existing second-tier banks through partnerships with licensed crypto brokers and trading platforms. These could provide tools for buying and selling digital assets. Such an approach would allow for a phased implementation — for example, beginning with a crypto trading platform in partnership with an existing exchange or custodial storage service, which would require smaller investments and allow time to develop expertise and a regulatory framework.

The emergence of a crypto-bank would primarily benefit financial institutions, while having little direct impact on the mining industry. Within the traditional banking system, miners are not typical clients. For example, if a miner were to approach a conventional bank offering mining equipment as collateral, bank staff would likely fail to understand its real value. In contrast, a crypto-bank with employees familiar with the technological cycle would be more capable of accepting such equipment as collateral, thereby enabling miners to obtain financing for equipment upgrades. Thus, a crypto-bank could expand miners’ access to financial instruments and stimulate sectoral growth. However, its main clientele would likely consist of crypto exchanges, brokers, and fintech companies — those most actively engaged with digital assets. Servicing these clients would enable a crypto-bank to achieve sustainable growth.

The success of any scenario depends on the position of the regulator — the National Bank of Belarus — and the development of clear “rules of the game”: criteria for selecting technological partners, lists of requirements for custodial providers, security and cyber-protection standards, and procedures for integrating trading platforms.

Although the creation of a full-fledged crypto-bank in Belarus faces significant challenges, the broader trend of integrating traditional financial systems with digital assets appears inevitable. The most probable path forward is evolutionary, beginning with pilot projects and partnerships that will allow the accumulation of expertise and the formation of a balanced regulatory environment.

Given these circumstances, the main direction of monetary system development in the medium term will likely involve hybrid solutions combining banking and fintech elements, with limited or no use of distributed ledger technology (DLT), but with active application of functions “inspired” by cryptocurrencies. These include cryptographic mechanisms ensuring confidentiality, auditability, programmability, and self-custody. One notable example is the joint initiative of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and the MIT Digital Currency Initiative — Project Hamilton — which demonstrated the technical capability of a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) system to process 1.7 million transactions per second.

When viewed through the lens of financial theory, cryptocurrencies without built-in stabilisation mechanisms, such as Bitcoin, are not liabilities of any entity. In contrast, CBDCs represent digital payment instruments denominated in national currency units and constitute direct liabilities of central banks. In the short term, initial CBDC issuances are expected to serve as an additional, third form of money — issued by central banks in digital form using distributed ledgers and cryptography. Over time, as CBDCs strengthen their role and increase their share of the money supply, they may enable a transition from an account-based payment system to a value- or token-based one. The critical issue in this transition lies in verifying the authenticity or value of a payment object independently of trust in intermediaries or counterparties.

This transition represents more than a mere change in the way money is created; it marks a transformation comparable to a shift in the very nature of money — from credit money to commodity money. As a result, the full-scale introduction of CBDCs will deeply affect monetary policy operations and instruments, as well as the procedures and conditions of central bank interactions with commercial banks.

Belarus is actively exploring the potential launch of a digital rouble, its own national CBDC. Its design is likely to lean towards centralisation — using permissioned DLT networks employed mainly by enterprises, governments, financial institutions, and consortia that sacrifice a degree of decentralisation and anonymity to achieve greater efficiency and compliance with business needs.

One of the advantages of wholesale CBDCs (used for interbank transactions between financial institutions with central bank accounts) is that they can be made available to a wider range of intermediaries than just domestic commercial banks. Allowing non-bank payment service providers (PSPs) to conduct transactions in CBDCs could significantly increase competition and innovation.

By issuing wholesale CBDCs as base settlement assets, central banks could facilitate the tokenisation of regulated financial instruments such as retail deposits. Tokenised deposits are digital representations of commercial bank deposits on a DLT platform. Depositors could convert their deposits into tokens and back, exchange them for goods, services, or other assets. Tokenised deposits could be covered by deposit insurance, but unlike traditional deposits, they would be programmable and continuously available (24/7), thus expanding their use in retail payments, including autonomous ecosystems. This, in turn, would facilitate the tokenisation of other financial assets such as shares or bonds.

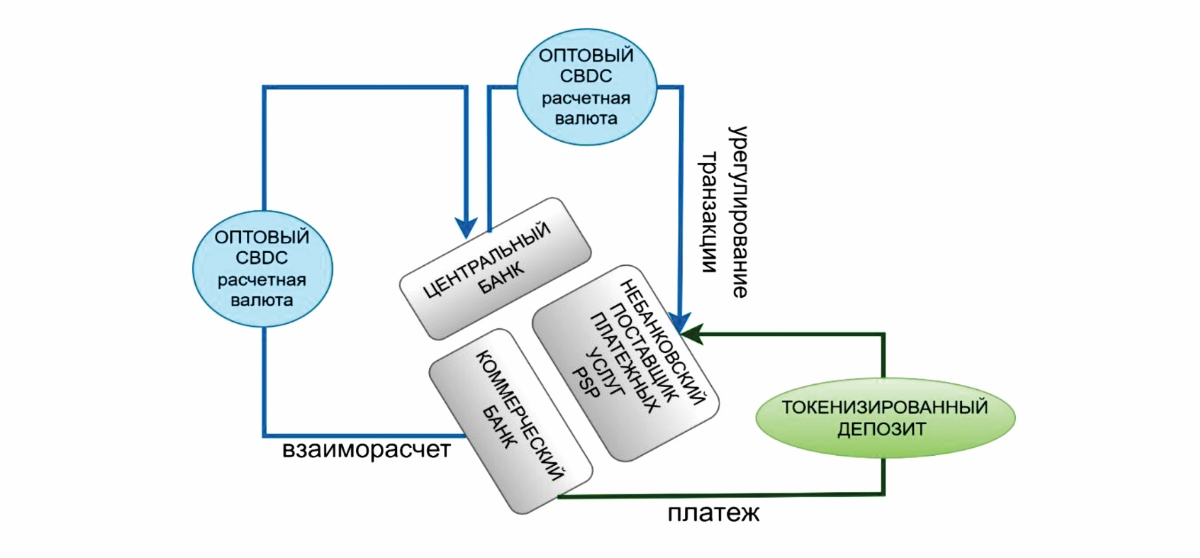

A possible system of tokenised deposits could include a permissioned DLT platform recording all token transactions issued by participating institutions — for example, commercial banks (representing deposits), non-bank PSPs (representing electronic money), and the central bank (representing central bank money). Retail investors (depositors) would store their tokens in digital wallets and make payments by transferring tokens between wallets. Inter-institutional settlements on the DLT platform would be executed using wholesale CBDCs as the settlement currency.

To illustrate this mechanism, consider a depositor holding bank tokens who wishes to make a payment to a holder of non-bank PSP tokens (representing e-money) to purchase a house. Both parties could agree that the payment (green arrow) must occur simultaneously with the transfer of property ownership. In the background, the bank would transfer wholesale CBDCs on the DLT platform to the non-bank PSP (blue arrows), which in turn would issue corresponding new tokens to its client’s wallet. All of these steps could occur simultaneously as part of a single atomic transaction executed via smart contracts.

In this system, wholesale CBDCs facilitate transactions and ensure the convertibility and uniformity of different representations of money. The same framework could also support the digital representation of shares and bonds. This would allow end users to access fractional ownership of such assets around the clock from regulated providers, and to settle transactions instantly.

For Belarus, as an industrial economy, the greatest benefits of digitalisation lie not in the financial sector itself, but in achieving end-to-end automation of interactions via CBDCs. Programmable CBDCs could support machine-to-machine payments within autonomous ecosystems. In this scenario, processes would increasingly operate without human involvement through the Internet of Things (IoT) — a network of connected devices. This entails not merely production automation, but a paradigm in which machines can purchase goods and services from one another and manage their own budgets. Consequently, top management will shift its focus from securing local orders to generating demand for products created across the entire value chain, as well as fostering innovation within that chain. The motivation for such activity will arise from transaction fees and preferential access to assets, ideas, and approaches within integrated value networks.

Since Belarus has officially become a partner of BRICS and a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), it is crucial for the country to develop a cross-border system of central bank digital currencies. The key element of a multi-CBDC system should be self-executing smart contracts, allowing participants to programme their transactions.

In such a framework, a return to the paradigm of decentralisation is expected, as smart contracts executed across multiple nodes are immutable, and transactions are settled only when predefined conditions are met. In securities trading, this automation can enable “payment versus payment” and “delivery versus payment” mechanisms — meaning that payments and deliveries occur only simultaneously or not at all. The acceleration of settlements and reduction of counterparty risk are essential characteristics for the international financial and payment system. This marks the beginning of a technically guaranteed international jurisdiction, enabling countries such as Belarus to unlock their scientific, industrial, and technological potential more actively.