Everyone has the right to take part in the governing of his country directly or through freely elected representatives.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The path to voting rights and, consequently, to democracy in its modern interpretation, was thorny for almost all leading countries. The honorary title of "model of democracy" was given only to those who walked on "hot coals".

Venerable thinkers had been dreaming of voting rights for many decades, but it is unlikely that they would want to see their ideas put into practice in their era. They preferred to leave their achievements to descendants.

The upcoming in spring 2022 presidential elections in France provide an opportunity to take a deeper look at inner working of both the evolution of voting right in Europe and the practice of a leading democratic state.

The first ideas about universal voting right appeared in France thanks to the famous representative of the Enlightenment, Denis Diderot, only 256 years ago. Up to the middle of the 18th century, the French avoided this important aspect of the functioning of the state. Diderot, despite his deep encyclopedic knowledge and concern for the needs of the people, was a ardent supporter of enlightened absolutism. He believed that popular masses were not able to understand political issues, so they needed a sovereign possessing supreme knowledge.

At the same period, the fundamentals of modern liberal democracy based on the principle of separation of powers, were laid in France. C. Montesquieu believed that political freedom consolidates society, and political stability is reached through affirming the equality of people which will be secured by the provision of a universal voting right. At the same time, C. Montesquieu recognised a certain amount of utopianism in his ideas, therefore he categorised three forms of government: republic, monarchy and despotism. In his opinion, the republican form of government is possible only in small states in terms of territory and population.

The Constitution of May 3, 1791 established a censored voting right for men. Only "active citizens" had the opportunity to participate in elections. The activity was confirmed, first of all, by the payment of direct taxes to the French treasury. Further, there was an obligation to take a civil oath and register with the military home guard. Thus, citizens who were antagonistic to the government were not able to be listed as "active", which significantly stabilized the political situation. A portrait of the electorate during the French revolution was as follows: the owner of the property, permanent taxpayer, French citizen who publicly expressed his support for the government. Actually, at the beginning of the 19th century, only a small number of citizens, just men, could take part in elections.

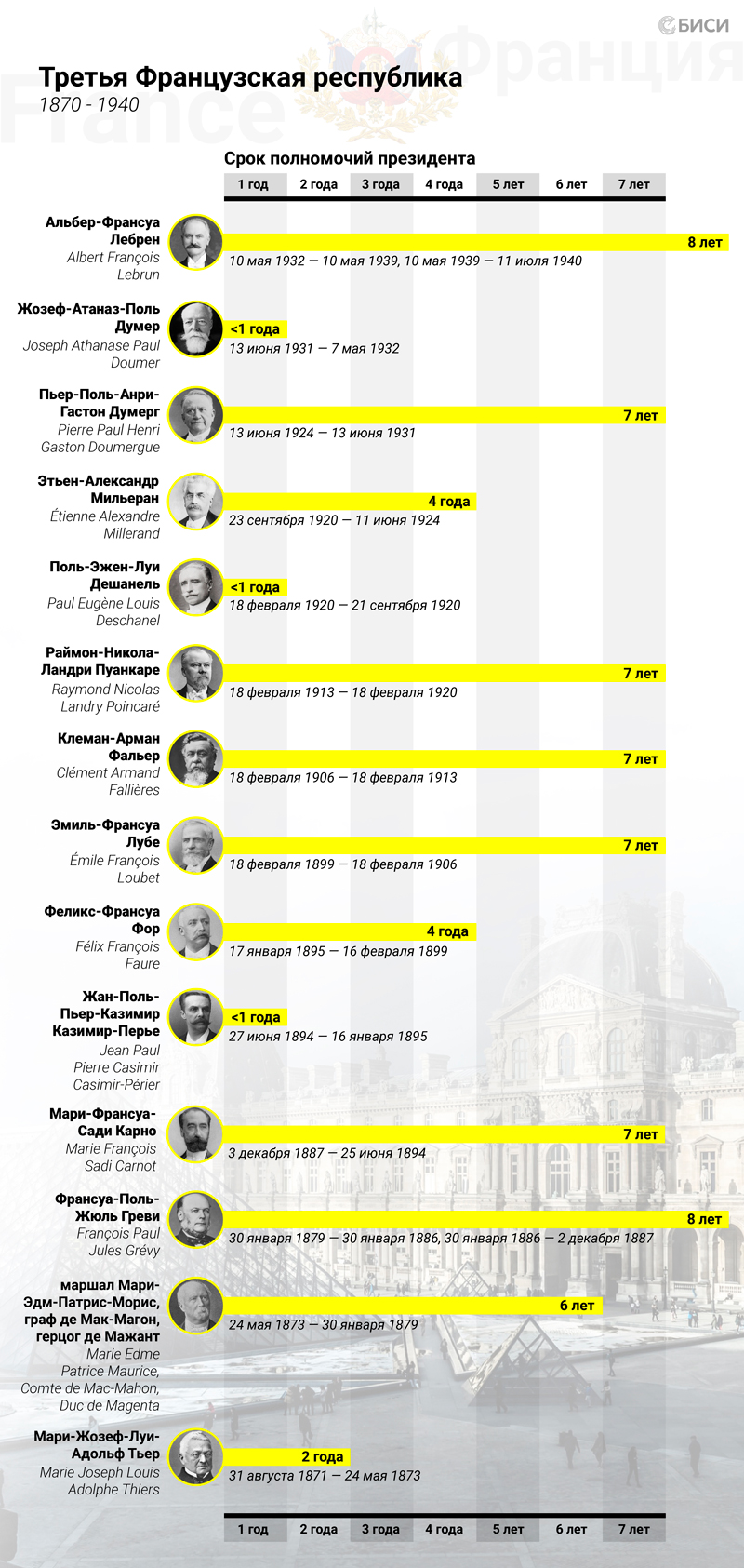

Direct voting right was fully introduced in France since 1848 already during the Second Republic. However, the list of exceptions was more than illustrative. It included women, military, inmates, clergy. The president of the Republic was elected by indirect voting by members of the French National Assembly (Senate and the Chamber of Deputies). According to the H. Wallon's amendment in 1875, the president had to receive a majority of votes, which in reality put him under the control of the legislature. As a result, of the 14 presidents of the period of the Third Republic, only 7 were able to exercise their powers throughout their tenure. This practice prevailed until 1958.

The lessons of the Second World War have left their mark for France. A new vision of the role of the president, the parliament, and a voting right was presented by the most famous name in French politics of the 20th century – Charles de Gaulle. His views, which later became known as Gaullism, were essentially aimed at strengthening presidential power and introducing "rational parliamentarism". With respect to voting rights of citizens, one may speak of a kind of revolution. In 1944, French women for the first time became full participants in the elections, in 1945 such privilege was granted to the military.

Today, the presidential elections in the French Republic are held every five years. The President is elected by direct universal suffrage. This right was granted to French citizens in 1962 after referendum initiated by Charles de Gaulle. This means that citizens aged 18 and over can vote, regardless of whether they live in France or not, and at the same time vote directly for a certain candidate. The term of office for the President is five years. The same person may not hold office for more than two consecutive terms.

To take a place on the ballot, potential candidates must receive 500 signatures from elected officials – e.g., city mayors or members of parliament. Also, candidates make a cash deposit of about € 1.5 thousand and submit a property declaration.

All candidates have a strictly defined amount of airtime on television and radio for election campaigning. Campaign-related costs are also limited.

If neither candidate gets more than half of the votes, the second round is held. Two candidates with the mightiest support of the voters participate in it. Based on results of the second round, the candidate who received an absolute majority wins the election. In the political culture of the French Fifth Republic, holding of the second round of voting is rather an anticipated event.

The Constitutional Council announces the official results of the second round on average within four days after the voting date. The president-elect inaugural ceremony takes place in Salle des Fêtes (reception hall) at the Elysee Palace. The new president is awarded the insignia of the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Elections in any country have always been a litmus test of internal political processes, the stress resistance of the state and society. Today, this segment is being consistently displaced by an external factor. The elections in their two parts, pre- and post-election, have become a full-fledged direction of foreign policy for individual states. The situation is noticeably complicated by the pandemic which has raised the degree in society. All of these factors have made the national political culture of democratic States to enter a stage of transformation.

In this connection, the key question is what will prevail: a democratic procedure or the preserving of a strong state?